A Lesson in Self-Defense from the Teachers of Bruce Lee’s Jeet Kune Do

NY Martial Arts Academy in Brooklyn, NY | Photo by Haeven Gibbons

Making a fist with my right hand and covering it with my left, I bowed before entering the training room. Five Fairtex punching bags hung on wall mounts that jutted out from the gray, exposed brick. The mirror made it look like there were 10. Above the mirror, words plastered on three posters made a list: Partiality, Fluidity, Emptiness.

Within the walls of the building covered in dragons and a mural of Bruce Lee surrounded by cherry blossom trees, instructors of the NY Martial Arts Academy teach Jeet Kune Do.

Jeet Kune Do is a modern martial art devised by the late American actor and martial artist Bruce Lee. The techniques and philosophies of the art form can be applied to real combat and challenging life situations.

The importance of self-defense is about being able to get yourself out of situations that may result in harm to you or a loved one, said Carlos Irizarry, a sifu, or instructor, at NY Martial Arts Academy and director of the Brooklyn location. He has been teaching at the academy since 2008.

Jeet Kune Do is rooted in kinetics and physics more so than traditionality, Irizarry said. Because of this, the practice is simplistic and efficient, making it useful for self-defense.

NY Martial Arts Academy training room | Photo by Haeven Gibbons

“When I move, you move. Got it?” Irizarry yelled from under his mask.

Irizarry inched forward, holding up a navy blue, oval-shaped target. Its edges were tattered from the familiar force of many punches before my own.

Pah! Pah!

I intercepted the attack.

The idea of intercepting is key in Jeet Kune Do. Jeet Kune Do translates to way of the intercepting fist. The idea is about being on the offense instead of the defense. The attacker always approaches the target, allowing the victim to intercept the attacking movement, Irizarry said.

“The principle comes from fencing and the idea that actions are faster than reactions,” Irizarry said. “The idea is that you’re waiting for the opponent to come towards you and offer you the opportunity to, in this case, hit the person, and that would be considered interception.”

But interception does not always work. Distance, timing, rhythm and finding the quickest way from point A to point B all play a role in determining if the victim will be able to intercept the attack or not.

“That’s why you still have to learn to block, cover or evade, by getting yourself out of the way,” Irizarry said. “The more opponents you have against you, the harder everything becomes. You would have to try to neutralize immediately so that you have less people or give yourself a chance to run in the opposite direction.”

Lee talks about neutralizing as quickly as possible and doing what you can to get yourself out of that situation, Irizarry said.

“At the end of the day, the purpose is to get home safe,” Irizarry said.

Following the onset of the pandemic, overall crime in New York City reached record lows in 2020, capping a two-decade decline of crime in NYC. But the city also started seeing significant upticks in violent crimes- homicides, shootings, burglaries and car thefts, according to the New York City Police Department.

The challenges of the pandemic strained police officers both mentally and physically. Officers faced diminished headcount and large-scale protests, sparked by the murder of George Floyd in May 2020. The unprecedented circumstances stretched the NYPD’s resources further than at any time in recent memory, according to a press release from the NYPD.

The NYPD saw a 97% increase in shooting incidents in 2020 compared to 2019, a 44% increase in the number of murders, a 42% increase in burglaries and a 67% increase in car thefts.

The New York City Police Department has continued to see an uptick in certain crimes across the city in 2021.

From April 2021 to October 2021, overall index crime in New York City increased each month, compared to the same months in 2020, except for in August 2021 where there was a decrease in overall index crime in the city, compared with August 2020. The decrease was driven by a 27.2% decrease in burglary and a 10.9% decrease in robbery.

Burglary was the only index crime to decrease in both April and May of 2021, while murders and shooting incidents also started to decrease from June through October of 2021.

But robbery increased by 15.8% and felonious assault increased by 13.8 % in October 2021 compared to October 2020.

With upticks in violent crimes throughout the city, it is more important than ever to learn self-defense, Irizarry said.

“I believe that self-defense still gives you a better chance at getting home safe if you found yourself in a situation where you have no other option but to defend yourself,” Irizarry said.

Pah! Pah! Pah!

Again, the target swung toward my face. An electric hiss met the silence as my synthetic leather glove smacked the worn, leather target. Other trainees watched as I intercepted each of our instructors' moves. But I felt like I was in a tunnel, hyper-focused on the next hit.

I hadn’t taken a karate class in more than 10 years.

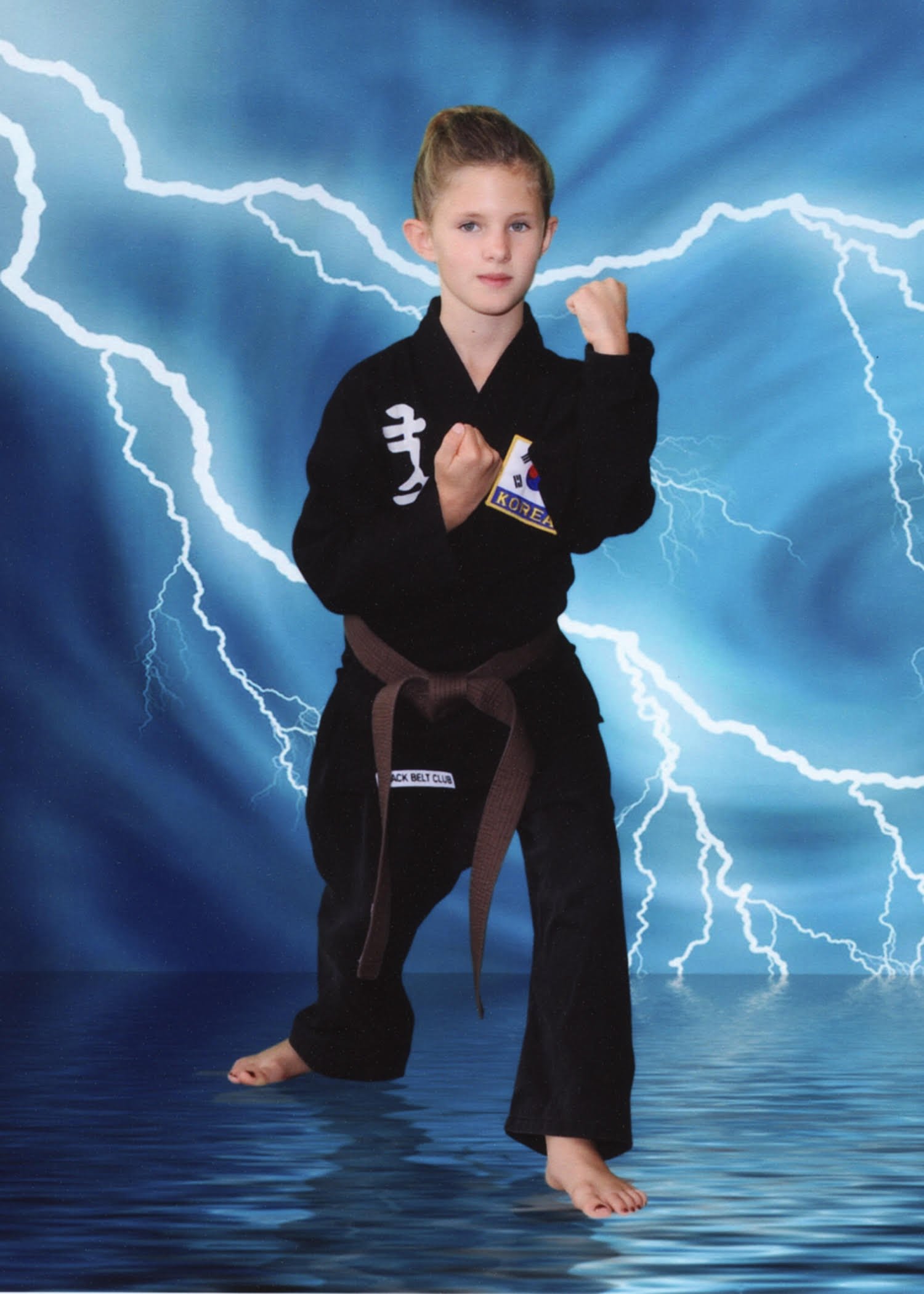

When I was in first grade my twin-brother, Dalton, and I started training in Korean traditional martial arts at a school called “Mu Sool Won” in Georgetown, Texas. We went to practice twice a week, every week until the fifth grade. I would rush to practice from my ballet class across the street and change out of m pink tights and black leotard into my dobok.

The uniform was a long sleeve robe tied with a belt. We wore long pants and no shoes. I would take the bobby pins out of my hair, releasing my ballet bun into a ponytail. And class would begin. Dalton and I practiced all the time: at the school and at home, in the front yard and on the trampoline. We tested for our next belt level every few months on the weekends.

Haeven Gibbons, then age 9, wearing a dobok and brown belt, the level before black belt. | Photo courtesy of Haeven Gibbons

After four years, we took the test we had been waiting for. The test to get our first-degree black belts.

We chopped boards in half with our bare hands and sparred each other, flipping our bodies so high in the air the mat barely seemed to cushion the fall. We felt like the most powerful 10-year-olds out there. But once our black belts were tied around our waists by our instructor, we never took a karate class again.

Pah! Pah! Pah! Pah!

The target moves faster.

But the back of my gloved fist hits the target before the target hits me.

The backfist punch is a classic Jeet Kune Do technique. So is the hook, straight lead and uppercut. Executing the technique properly is all about knowing how to position and use the force of your body to make the hits more powerful, and it’s about not letting your opponent know what is coming next, Irizarry said.

Three other people trained at the academy with me on that Saturday afternoon in early October. They nodded as Irizarry taught. One woman who didn’t stand taller than 5’3” punched at the air. She had a muscular build and short, bleach blonde hair that barely moved as she hit the invisible attacker.

Everyone came to the academy for different reasons but learning self-defense was a common one.

“I wanted to learn how to defend myself in a way to keep not just myself safe but the people around me safe,” said Jamal Jones-Brewster who has been training at the academy since 2013.

I too spent my Saturday afternoon in the gym hoping to brush up on my self-defense skills. After over 10 years of no practice, I probably wouldn’t even rank as a white belt, the lowest belt level in Korean traditional martial arts. My brother and I stopped training after we claimed our black belts because we thought the belt meant we mastered the skill and that we would always be able to remember our moves. But karate isn’t like riding a bike.

Haeven Gibbons and her twin brother, Dalton, practice in class. | Photo courtesy of Haeven Gibbons

Haeven Gibbons, then age 6, flips her opponent. | Photo courtesy of Haeven Gibbons

“It’s about repetition,” Irizarry said. It’s an art, and progress comes with doing the technique, the right way, over and over again, he said.

Pah! Pah! Pah! Pah!

The kicks pierced my side. The strikes were hardly blocked by the mat that I held like a shield. The drill was simple. One person held a mat at their side while the other kicked the mat as hard as they could. Julia Cassidy was my partner.

“Don’t use your toe!” Irizarry shouted at Cassidy.

It’s important to kick with the top of your foot, he said.

It was my turn.

I felt discombobulated aiming for the target while trying to hit it with force. This motion, that was once so familiar, was now foreign.

But that was OK. I had walked through the old wooden doors of the dragon-covered building on Eighth Street because I knew I needed to get better.

“It’s about making people better, there's something satisfying about seeing somebody who has never trained before start to get better and also making sure that good people are learning to defend themselves because there's a lot of bad things out there in the world,” said Kevin Feijoo who started training at the academy in 2013 and became an instructor in 2017.

One of Feijoo’s students, Muarem Kurtali, has been studying at the academy for three years. He said the training has prepared him to use self-defense if he ever needs to.

“I first started because I was a big Bruce Lee fan since I was a young kid,” Kurtali said. “Not only that, but I've always wanted to study JKD ever since I was a child. I've always had this one question, ‘What can be the best martial art, the best self-defense system?’ and that was a question that was always through my mind.”

At the age of 13, Bruce Lee began studying wing chun gung fu under wing chun master, Yip Man. He moved to Washington State at 18 and began teaching gung fu in Seattle. At 21, he opened his first school, the Jun Fan Gung Fu Institute. Two more schools followed in Oakland and Los Angeles. By the time Lee was 27, he had developed his own martial art from the techniques he learned under Yip Man.

Lee was a martial arts master and a Hollywood success, starring movies like Fist of Fury, Way of the Dragon and Enter the Dragon. To some, he is an icon.

Lee was an inspiration for many popular martial artists and fighters including boxing and MMA legends like Manny Pacquiao, Sugar Ray Leonard and Mike Tyson. His teachings have inspired people from all careers and backgrounds around the world.

Lee became the first Chinese-American man to star in a Hollywood movie, and before the 1973 movie Enter the Dragon, there were few martial arts schools in the United States, but by the 1990s, 20 million Americans were studying the discipline. His influence made an impact on the culture in America.

Partiality. Fluidity. Emptiness.

The words plastered on the three posters hanging above the mirror in the training room were Lee’s stages of cultivation, a symbol representing each stage. Partiality is the stage of recognizing that you have lots of extremes and are experimenting what works for you. Fluidity is reaching the point where you are able to take what happens as it comes, and emptiness is the formless form; when you exist in a stage of reflex and let go of all technique. The stages relate to both combat and life.

A fourth poster hung above the three.

The fourth poster showed a yin yang symbol surrounded by arrows and Chinese characters. The colors and design of the symbol represent all three stages of cultivation. The Chinese characters translate to using no way as way; having no limitation as limitation, the main principle of Jeet Kune Do.

The guiding concepts of Jeet Kune Do are simplicity, directness and freedom. Lee made sure the physical techniques and philosophies of the art would not limit its practitioners. The art is about repeating a simple motion, the correct way, over and over, so, in a combat situation, the challenged person can respond without thinking. Jeet Kune Do celebrates self-expression over any organized style rooted in tradition.

“What this art means to me is it makes me whole because you get to know self-defense, and, at the same time, you also become a better person,” Kurtali said.

Jones-Brewster said he started training in Jeet Kune Do to learn self-defense, but he stuck with it because of the mental health benefits.

“I noticed the mental health benefits I was gaining from it,” Jones-Brewster said. “It became a place where I can get out a lot of frustrations. I started to notice, over time, I was getting angry less, because I was able to handle day-to-day situations in my life in a more efficient and direct manner. I also noticed that I was able to handle conflicts better than I was prior to going to training, and overall dealing with day-to-day issues became less of a stressor for me.”

Cassidy, who was bored with her gym workout, attended the class because she wanted to engage in something more interesting and learn the philosophy behind Jeet Kune Do.

“For me, it's about knowledge. I wanted to learn the theory behind all the physical movements, and this kind of exercise gives you a strength inside of you, so you can be more confident.”

Making a fist with my right hand and covering it with my left, I bowed toward Lee’s symbol before exiting the training room. The fist represents power and the hand that covers the fist represents knowledge.

Without knowledge and a good mind and heart, you have no power, Irizarry said.

I left the dragon-covered building and turned right on North Eighth Street toward Bedford Avenue Station to catch the G train headed home toward Church Avenue, back to downtown Brooklyn. Walking through the Williamsburg neighborhood, a new sense of confidence and peace ran through my bones.