Abraham Lincoln wants YOU

Some call Steven Spielberg's Lincoln one of the greatest movies of all time, and others hail it as a truly bipartisan American film. It's hardly either, but it is a movie well worth seeing for all those who enjoy history and rooting for America, regardless of political stripe. The film follows Abraham Lincoln through the final days of the civil war in his desperate push to pass the 13th amendment--permanently abolishing Slavery in the United States. Through political maneuverings, sometimes dodgy, always chancy, Lincoln and his cabinet fight the corrupt political landscape of Washington to deliver the bill that became a righteous landmark in American history.

To say this movie is timely is like saying J.K. Rowling sold a lot of books. And that's part of it's appeal. Audiences easily recognize the partisan divide (with jabbing references to "Republicans" or "Democrats" throughout, one’s theater etiquette may be as telling as a ballot, and the controversy of a president trying to pass what he feels is human rights legislation. Much of the movie, particularly the long scene with Lincoln and his cabinet, seems a defense of President Obama's first term. The filmmakers try to limit scenes like that, mostly with success.

The story has morale by nature. Lincoln is the American hero who took the road less traveled, or scraped down it. But to combating the American loyalty to Lincoln, the film takes brave, conservative stances sometimes. It stakes that war is better than peace if peace means triumph of evil. Then it wages that people are equal before the law but not in "all things" such as character.

It’s safe to say the Academy already has a few Oscar statues etched with "Lincoln." Jared Harris’ Ulysses S. Grant is spot-on perfect, but Tommy Lee Jones steals the show as the grouchy and honorable Radical Republican Congressional leader Thaddeus Stevens. (Robert E. Lee however, sadly gets a cameo and no speaking part).

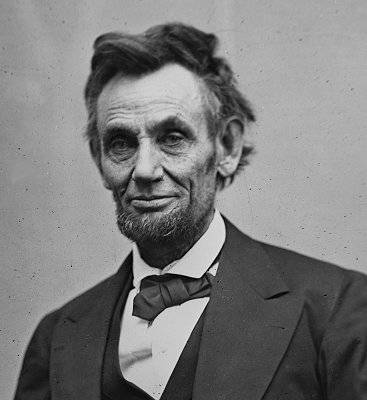

The movie’s success obviously hinges on the portrayal of Lincoln. Daniel Day-Lewis' Lincoln is at once a principled man burdened by the times and his responsibilities, and a folksy farm boy who tells stories and jokes to make points (often to the hilarious frustration of his cabinet). He is everything both our collective conscience and historical record demand he be. Indeed, the filmmakers do a remarkable job of showing the dark sides of Lincoln's personal life while not marring our ability to admire the man. Mary Todd is another story, although to their credit, the film subtly chastises historians who only remember her bad side.

But despite this, the film feels often flat and formulaic. There were obvious exceptions, like Thaddeus Stevens' dramatic scene in the house, which moved this critic tears. But that was not the norm.

Paying Lincoln homage is an American tradition, but this film stretches the trend. It lionized him to a point of deification, only to fall into self-parody. He is constantly lit to look like he has a halo, making him up to seem unreal and immaculate, like an angelic grandfather. This is strange for Hollywood, which prides itself on its commitment to complexity in historical figures.

Other flaws might arguably fall into a slightly more offensive category. Ironically for a film all about racial equality, the black characters in the story seem only present to make white people feel guilty or affirmed--either with an innocent puppy-dog pout or a wise-looking smile. Christianity makes a strong case for slavery (a historic absurdity). Copperhead Democratic Congressman Fernando Wood refers to God making men “unequal,” and Thaddeus Stevens' only counters with “Nature's Law.” In fact, a less religious sounding geometric argument replaces Lincoln's famous argument against slavery through intelligent design.

The question presses: why see a modern interpretation, and too much argument, devastation of one of America’s most heroic stories? Why let Hollywood bring a legend back down to size? To bring it close to home. The film chronicles that great men have lived, and it inspires that great men can live still. That message could kick start the next American legend.